Christmas was barely celebrated in the early part of the nineteenth century. It was not considered a public holiday and traditionally the giving of gifts was practised at New Year. However, come the end of the century, it was the biggest annual celebration in the British calendar. Workers had gained a two-day break (including the 26 December, Boxing Day) and the advent of the railways ensured that family members could travel home to spend Christmas Day with their families.

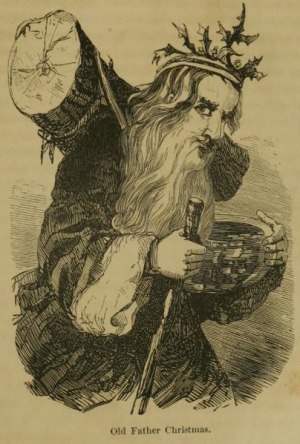

Father Christmas

Old Christmas was usually depicted as a thin old man. He evolved from pagan mid-winter traditions wearing a dark green cloak and a wreath of holly, ivy or mistletoe on his head and heralded the coming of spring. In Saxon times he was known as Father Time, King Frost or King Winter. It was thought that being kind to King Winter would promise something good and so he became associated with the receiving of good things.

Old Christmas grew portly with the Viking representations which derived from the Norse god Odin. This Father Christmas gave gifts to the good and punishments to the bad. The Normans brought with them the story of St Nicholas and the merging of St Nick and Father Christmas began.

The first written reference of Father Christmas can be found in a fifteenth century carol. In Tudor and Stuart times his name changed to Sir Christmas and Captain Christmas. But then the Puritans banned the frivolities of Christmas in the mid seventeenth century. Old Christmas was still the prevalent figure during the early nineteenth century.

The later Victorian Father Christmas dressed in a cloak or suit that was green, blue, brown or red and was the epitome of the jolly, benevolent Father Christmas of today, who brought gifts and cheer to children.

Dutch Sint Nicolaas, or Sinterklass, became Santa Claus in the U.S.. His feast day was usually celebrated on 6 December but the Americans adopted Christmas Eve to kickstart their Christmas. By the 1820s Santa Claus was travelling on a sleigh guided by reindeers and by the 1870s his garb was bright red. By the late 1880s Santa had merged with Old Christmas in Britain and became a symbol of the practice of gift-giving at Christmastime.

Christmas Card

The Christmas card was first sent in 1843. Sir Henry Cole, the first director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, commissioned the artist J.C. Horsley to design 1000 festive greetings cards – he sold the remainder to the public, but at one shilling each, they were far too pricey for the ordinary citizen.

Printing processes improved during the century and therefore more affordable cards could be printed and sold to the general public, enabling many more people to send the now traditional Christmas card. The implementation of the penny post in the 1840s, when the sender paid for postage and not the recipient and then the half-penny post in the 1870s, when the railway infrastructure again benefited the public and helped reduce costs for the Post Office, made the sending of cards a more attainable pastime for the lower paid in society. The proliferation of post boxes in which to deposit cards also helped enormously in popularising sending seasons greetings on cards

Christmas cards from 1870 and 1855, respectively

Christmas Cracker

The Christmas cracker was invented in the 1840s. Sweet shop owner, Tom Smith, was inspired by French bon bons (wrapped sweets) on a trip to Paris. The original cracker contained sweets wrapped in chemically treated paper that made popping noises when unwrapped, they were called ‘fire cracker sweets’. He further developed his cracker to introduce the explosive ‘bang’ in the 1860s and the cracker that we decorate our festive tables with was born. The sweets were replaced with a joke or a motto and a trinket, and by the 1880s a paper hat, it has become a traditional element on the festive table.

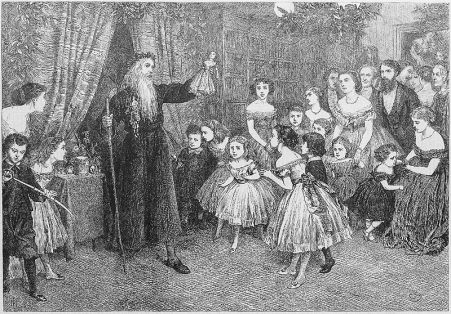

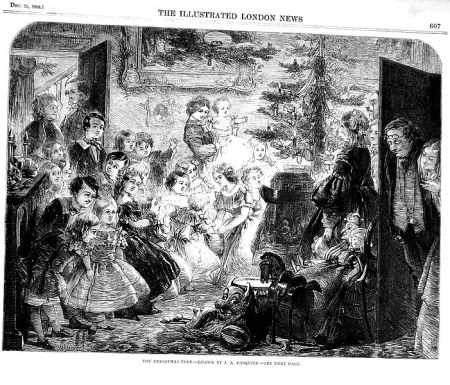

Christmas Tree

Decorating homes with boughs from evergreen trees was a pagan and Christian tradition that represented Christmas and the everlasting life with God and the winter solstice on 21 December. They would be decorated with fruit, ribbons and paper flowers and often placed in windows. Indeed, ‘deck the halls with boughs of holly’ was a Welsh carol that originated in the sixteenth century. It was recorded that the German Queens of the eighteenth century had brought trees inside and decorated them, as was the custom of their homeland, but it wasn’t popularised until the Victorian age.

It is often thought that the indoor Christmas tree was a custom brought to Britain by Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort. However, it was a practice that was occasionally observed by German immigrants in Britain and its appearance was growing in the 1830s. It was popularised in 1848 after Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were shown in Illustrated London News surrounding a tree, perched on a table-top, resplendent with ornaments hanging from branches that glistened in the candlelight. The scene also depicted the younger members of the royal family gazing at it in awe.

Advertisements for tree decorations appeared from 1853. Increasing industrial mechanisation meant that mass-produced brightly coloured ornaments were more affordable to the general populace. Also, the rising middle classes had some expendable income to decorate their homes, much like the royal family.

Christmas Stocking

The Christmas stocking appeared around 1870. As the second half of the nineteenth century progressed children’s toys became more affordable, as along with the production of cardboard for Christmas cards, and manufacturing processes for decorations, toy manufacture became more wide-spread. Previously toys had been hand-made and therefore expensive. As the century progressed toy usage filtered down the social hierarchy and middle-class children were able to have toys in stockings that previously only the rich could afford, such as books, dolls, board games and clockwork toys. Poor children would still only find some nuts and pieces of fruit, maybe an apple or orange, in their stockings, both if they were lucky. Children from more affluent families received a toy along with the fruit and nuts.

Christmas Turkey

Whilst feasting at Christmas was common for centuries, it was during the Victorian era that the meal we know today appeared. Previously, other roasted meats formed the centrepiece of the Christmas table, such as beef and goose.

Before railways, the turkeys had to be herded from Norfolk to London to be sold at market. The journey lasted around three months. They would get sore feet from walking long distances and so wore little leather shoes. When they reached their destination, they would have reduced a large amount of weight and so needed to be fattened up again before market. This ensured that they were an expensive food source and not available to the masses.

However, the emergence of the railways meant that livestock could travel to market swiftly, in relative comfort, which reduced the costs of keeping the birds, thus lowering the price of turkeys for the ordinary Briton. The turkey, judged to be the perfect size for a large family gathering became the country’s preferred choice by the end of the century and was popular with the rising middle classes.

Christmas Carols

The carol as we know it today developed from seasonal songs first sung in the thirteenth century. However, Puritan Britain banned celebrating Christmas and so the festival of feasting and singing declined. ‘While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night’ (1698) and ‘Hark the Herald’ (1782) were written during the revival of the tradition, but it was around the 1830s that carols appeared on broadsides, for families to read and sing together.

It was the from the late 1840s that anthologies were produced that were essentially transcriptions of songs that the working classes would sing. They were packaged in such a way to appeal to the middle classes who bought them to enjoy during the festive season. Fast forward to the 1870s and with even more disposable income for the middle classes and payment plans now readily available, pianos appeared in homes to enable families to have a Christmas sing-song.

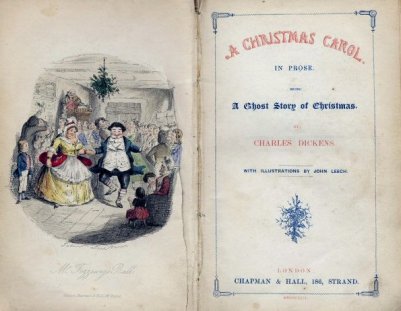

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens did not invent Christmas, but A Christmas Carol, written in 1843, popularised many of the customs that we know and love today.

If you want to read more about Dickens’ A Christmas Carol see A Home Place Web’s post here.

Images: Wikimedia Commons

Sources

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/victorian-christmas

http://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/A-Victorian-Christmas/

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/victorian-christmas-traditions

http://www.bbc.co.uk/victorianchristmas/history.shtml

http://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/christmas/santa.shtml

https://www.whychristmas.com/customs/trees.shtml

Super post

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ruby, thanks for the link to my blog on Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol. The PR is much appreciated, as I asked Santa for more reader/followers for Christmas!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I was going to mention it last night(ask if you minded – but then I thought ‘what if I don’t finish the post?’ And then I thought we wouldn’t share our blogs if we didn’t want them read! Happy to do it – never done it before! Have a wonderful Christmas 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You have enlightened me. Thank you and merry Christmas.

LikeLiked by 2 people

🙂 Merry Christmas to you too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderfully comprehensive Christmas compendium! Love the illustrations. Here in ultra-Christian America, people look askance if you try to explain the pagan roots of the holiday. I’ll just send them to your blog. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fab! This was last year’s post when I had more time and had always planned to share it again. I took a night off from blogging last night! I really enjoyed the write up and research and I’m so glad you liked it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t imagine being the person to put all those booties on the turkeys!

LikeLike

A very informative and interesting post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Christmas was not a public holiday in Scotland till c1958!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! Hogmany was the primary event, wasn’t it? My husband’s family remember first-footing fondly. A couple of years ago we surprised my sis-in-law at midnight 🙂

LikeLike

It was (though I grew up in England so had different traditions). Now both Christmas and Hogmanay have succumbed to the same commercialised hype as everywhere else.

LikeLike

Merry Christmas Ruby in keeping with the situation. I am loving your Christmas posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you and Merry Christmas to you too! I’m trying to keep the posts as diverse as possible 🙂

LikeLike

I don’t know where I read it (lol it might have been one of your own posts) but didn’t something outrageous happen one year on the 12th day – and Queen Victoria was so horrified by the excessive drinking and rioting she changed the way the holidays were held?

I am a bit foggy about what exactly happened but I believe the way the holidays are held today is very much down to Queen Victoria.

LikeLike

This is so interesting! Happy Christmas, Ruby! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Merry Christmas 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person