The 1851 Act regulated the sale of arsenic by imposing a series of measures aimed to ultimately control the arsenic panic that gripped the country. The six parts to the Act covered:

- On every Sale of Arsenic, Particulars of Sale to be entered in a Book by the Seller in Form set forth in Schedule to this Act.

- Restrictions as to Sale of Arsenic

- Provision for colouring Arsenic

- Penalty for offending against this Act.

- Act not to prevent Sale of Arsenic in Medicine under a Medical Prescription.

- ‘Arsenic’ to include Arsenious Compounds.

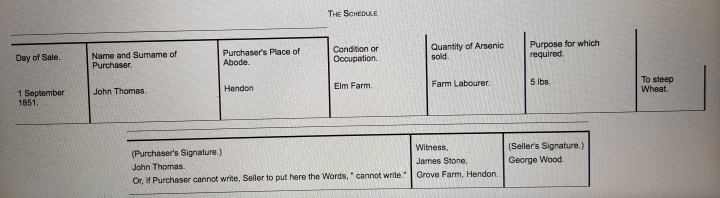

The Act prohibited the sale of arsenic to a potential purchaser unless previously known to the vendor or in the presence of a witness known to both parties. All arsenic sales were to be recorded in a poison register stating the date of sale, quantity of arsenic sold, purpose of purchase, name, address, condition or occupation of the purchaser, both parties were then required to sign the register. If the purchaser admitted to being illiterate or unable to write then the vendor must endorse the register with the phrase ‘cannot write’. It also required the purchaser to ‘be of full age’, i.e. twenty-one.

Arsenic could not be sold unless it was mixed with soot or indigo – one ounce of soot or half an ounce of indigo, (i.e. black or blue) – at the least to one pound of arsenic. The ratio of soot and indigo were to be altered with larger or smaller sales up to the quantity of ten pounds in weight. The arsenic was to be adulterated with soot or indigo to prevent accidental poisonings in domestic situations and to alert would-be victims that their food or drink had been tampered with.

To offend against the Act risked a fine upwards of £20, around £1,170 in 2005 according to the National Archives website, you can access their Currency Converter here. The Act also provided instructions for the supply of arsenic prescribed for medical use by a ‘legally qualified Medical Practitioner, or a Member of the Medical Profession.’ Wholesale dealings were also governed by the Act, which required orders in writing. For clarity, any arsenious compound was to be included in the definition of arsenic in the Act.

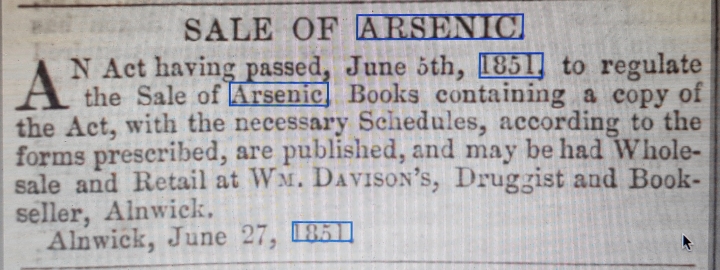

The Act, whilst going through Parliament in early 1851 was the subject of several suggested amendments, one of which was to control the sale to men only. Women, being considered the sex most likely to poison, either by design, or accidentally when in domestic service. This amendment failed to make the final Act after many women protested against this further restriction on their legal rights. On 5 June 1851 the Sale of Arsenic Regulation Act became law.

Regulation covering the sale of arsenic was deemed essential as criminal poisonings had increased remarkably during the first half of the nineteenth century. The number of trials in the 1830s was triple the number of trials in the 1810s, for example, and then increased again by a further fifty percent during the next decade. Arsenic was the would-be poisoner’s method of choice for around seventy percent of trials during the 1840s. The sensationalist press, itself growing exponentially throughout the nineteenth century, eagerly reported news of suspected poisonings, criminal or accidental, to its readership, encouraging the idea that the country was in the grip of an arsenic panic.

The Act’s success has been doubted as anecdotal evidence proved that prior to pharmaceutical regulation the law was flouted on numerous occasions; for example, the purchaser needed a smaller supply that the vendor failed to register, or the purchaser ordered the largest quantity, which was assumed to be needed for industrial use and therefore not required to be adulterated with prodigious quantities of soot or indigo.

My study of nineteenth century poisoning crimes tried at the Old Bailey in London highlighted that arsenic was the poison used twenty times during the century; seventeen times before the Act of 1851 and only three times in the second half of the century. With this admittedly small cohort, the efficacy of the Act in reducing cases of arsenical poisoning is proven, however poisoning cases at the Old Bailey rose overall throughout the second half of the century and the research suggests that would-be poisoners chose alternative poisons to commit his or her crimes. Indeed, it could demonstrate that regulations were enforced more strictly in the metropolis and less so in other towns and cities or in rural settings.

There are many fascinating themes to explore when examining the reasons why people died of arsenic poisoning during the nineteenth century, or indeed from other substances that were the conduits to induce injury or death, beyond the scope of this short article. However, recommended are the two books below that will further elucidate historic criminal and accidental poisonings.

Sources and further reading:

The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work and Play, James C. Whorton

Poison, Detection, and the Victorian Imagination, Ian Burley

http://www.britishnewspaperarchives.co.uk

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1851/13/enacted/data.html

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/results.asp#mid

Interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another great post Ruby! 🙂

Bloomin’ cheek that women were deemed most likely to be poisoners though! 😉

Lizzie

LikeLike

As always you have provided very interesting historical facts. Thanks for sharing

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. There was an interesting fact on TV the other night that prompted me to repost – traces of arsenic can be found in rice! Apparently they test baby rice cakes but don’t test baby rice . . .

Also, my dietician neice told me that children under 5 shouldn’t have rice milk because of this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing. One should be careful, what stuff the put in what we consume?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The arsenic occurs naturally in the rice – a trace element from the soil in which it is grown. It also occurs globally and not limited to any location.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The first I learned of arsenic was in Agatha Christie’s books. We read about it in med school too. But what we hear about the pollutants in water, soil, fertilizers and air are mind boggling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glasgow had its famous Madeleine Smith case in 1857. The chemist where she allegedly bought the arsenic is long gone, but the site features in one of our Women’s Library walks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read an academic study of that case back in 2013 when I was researching the subject. Of course, I watched Scotland’s Murder Mysteries on a number of occasions, too. I’ve never thought of tracing her steps when in Glasgow.

LikeLike

We also visit the lover’s grave on another walk. The fiancé is in the Necropolis. Her house is still standing and her father designed the MacLellan Galleries so there are quite a few traces.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll have to pay a visit one day and go to all the places I never remmber to go to – maybe when my husband is up for the football.

LikeLiked by 1 person