As World War One drew to a close, a new terror materialised that would more than double, and some suggest treble, the 16 million people killed during the conflict. A deadly global pandemic was facilitated by an airborne virus, the movement of troops around Europe, global commerce and migration. More died in a single year than four years of the black death, or bubonic plague (1347-1351). One-fifth of the world’s population was affected by ‘Spanish influenza’. It killed more people than any other illness in history and it is estimated that more than 20 million, and up to 50 million people died. It was a strain of influenza so virulent that people died within hours of presenting with symptoms and claimed victims from every continent.

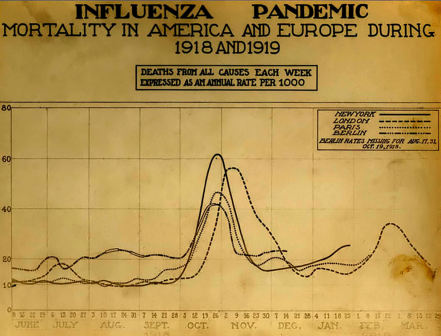

During the late spring and early summer months of 1918, it was noted that en-trenched soldiers became ill with what was called ‘la grippe’, the symptoms manifesting as sore throats, headaches and appetite loss. The close quarters of the trenches gave the virus ample opportunity to transmit to comrades, however, recovery was usually fairly rapid and the doctors initially called it ‘three-day fever’. Spanish flu presented itself in three phases, the first showing milder symptoms than was seen with the later more virulent pathogen. Another wave forged its deadly path from August to December the same year, with the demobilisation of troops. Its third phase ran from January to April 1919, running its course as most victims had died or developed immunity.

Discourse continues on the origin of Spanish influenza. The name ‘Spanish flu’ arose due to the reporting of demoralising stories being proscribed during WWI, resulting in earlier cases not making the news. Spain was neutral during WWI, therefore its journalists were not under the same constraints as those belonging to countries engaged in conflict. Spanish flu is something of a misnomer if modern research is correct, which suggests that Spain was not the ground zero for the virus, and just the unfortunate first known reporting of the disease. Spanish wire news service, Agencia Fabra, sent news to Reuters headquarters in London. ‘A strange form of disease of epidemic character has appeared in Madrid. The epidemic is of a mild nature and no deaths have been reported.’ It is argued that a possible cause of the early spread of the disease comes from the transient Spanish and Portuguese unskilled workers who travelled by train to France, as young fit Frenchmen were engaged in war work.

The Scotsman reported on Monday 24 June 1918, that Spanish influenza had been reported for ‘some time past’. They stated that it was ‘ordinary influenza’ that spread ‘with the rapidity of an epidemic.’ Dr Legroux, of the Pasteur Institute, said, ‘It is not a serious malady. It began at the front in early May. From Dunkirk to the Vosges most of the soldiers were attacked by it, and the Germans were not immune. it is very infectious. The infection spread to Paris and then to Spain. The Spaniards made a great fuss about it. But for that it would not be noticed today.’ However, Dr Legroux may have come to regret his words once the world was in the grip of the ‘Spanish lady’, as Spanish flu was also known.

The same week The Dundee Evening Telegraph reported that some schools were closed in Wales, affecting 600 pupils, as several teachers had become ill. Highlighting the ease in which the illness could be spread around the world, an Indian seaman died in Hull after contracting Spanish flu onboard ship. The disease was also prevalent in Belfast where it was reported that the epidemic was spreading. Alarmingly, facts emerged about those suffering at the Belfast Workhouse, revealing that the ‘victims’ bodies turned black as coal’ within half an hour of death.

The chief medical officer of the Local Government Board, under the title of Public Notice, stated in the Sunderland Daily Echo on 1 July, that ‘all possible precautions should be taken: one case today may mean a hundred tomorrow.’ With no available cure, public health awareness campaigns concentrated on prevention of infection. Advice in the Tamworth Herald on 6 July 1918, advised the public to spray their homes and workplaces with Jeyes’ Fluid as ‘prevention is better than cure.’ What was worded as advice, was a thinly disguised advertisement for the disinfectant, as no other ‘so-called’ disinfectant would be able to do the same job as Jeyes’, for they were ‘quite useless.’ And by Tuesday 9 July, The Stirling Observer reported that Spanish influenza was ‘pretty rife’ with many cases in the town. Establishments that were already short-staffed due to the war were struggling as their workforce fell ill. Sales of quinine increased as it was recommend as a preventative measure against the flu, whereas Formamint tablets were recommend for patients already infected.

As troops returned from France, they embarked on train journeys home, enabling the virus to be spread throughout the country. Surprisingly, it was not just the very young and the frail who were victims, young adults between twenty and thirty-five years old succumbed very quickly to the disease. Modern study suggests that this is because they had not gained the necessary immunity that older generations had gained having been exposed to many different influenza viruses over the course of a lifetime. The onset of Spanish flu was extremely rapid and those healthy at breakfast could be dead by the end of the day. Some patients developed complications from the initial symptoms, such as pneumonia and cyanosis, which signalled that the patient was not getting enough oxygen. Eventually the lack of oxygen would lead to suffocation.

Treatment of Spanish flu was limited prior to the advent of antibiotics for bacterial complications and antiviral medicines for influenza. Hospitals were overwhelmed with the influx of patients coupled with reduced staff, for they were also affected by the disease, and drafted in medical students to ease the load. One quarter of the British population was affected during the epidemic of 1918/19 and the death toll was 228,000 in Britain alone. In America, the average lifespan fell by 10 years in the space of one year. Additionally, the 15 – 34 age group dying from Spanish flu and its complication pneumonia, was twenty times higher than previous years and an estimated 675,000 people died from the disease. Insufficient record keeping across the world, either due to the escalating disaster or poor administration, means that there is not an exact total of deaths caused by Spanish flu, for it reached remote villages along with major cities. However, with an estimated third of the world’s population affected by Spanish flu, some 500 million people, the deadliest pandemic has been proven to be the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918/19.

Scientists today are using the study of Spanish flu to enlighten them about the pathology of viruses. Their research may result in a change in the way vaccines are formulated. Rather than following the frequently mutating strains of influenza virus, they could base a vaccine on strains that people did not become immune to as children.

Suggested sites:

http://www.britishnewspaperarchives.co.uk

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/04/140428-1918-flu-avian-swine-science-health-science/

http://time.com/3731745/spanish-flu-history/

All images Wikimedia Commons

I didn’t realise so many people died. I’d like to think that this may not happen like this now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In theory it shouldn’t. Modern hygiene standards and medicines should help prevent infection and preserve life. However, globalisation does mean that any virus can spread worldwide in a matter of hours. It is thought that the Spanish flu was possibly a mutation from avian and swine influenzas that were able to merge with a human strain and that was what made it so deadly.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I found this fascinating. Had no idea it was so deadly. Thank you for sharing Ruby!

LikeLiked by 2 people

So glad you enjoyed it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great when I am studying Infectious Diseases! ^.^ Enjoyed the details you put forth, and the descriptive tone in them 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fab! You may like the links I added then. They (obviously) feed to other links too. A bit more science related than I found necessary. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting read! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 2 people

so many people died from this flu. Never got to read deeply about this flu but this post was well written.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A huge tragedy, straight after the war – as if the world had not suffered enough.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So interesting and informative – I love reading posts on historical disasters – especially pandemic illnesses! (is that slightly macabre?!)

LikeLiked by 2 people

A little! Probably no more than me when I have to watch documentaries about historic disasters. Thanks for your comment 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent read…..my uncle Charlie almost died from the Spanish flu on the front lines in 1918 and had to convalesce in a British hospital before returning home. (see blog for pics) A few years ago (2010?) when the H1N1 flu was circulating, and the world health officials were scared of another pandemic, I was unfortunate and caught it two days before the vaccine came out, and it was the sickest I have ever been, not in danger of dying, but two weeks of pure misery and a long six week recovery.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Poor you, my son had a dose of swine flu – had him laid up barely able to move.

I’m so glad you liked the post. And your poor uncle Charlie, considering how many people were affected I’m surprised I haven’t heard of it in my family history (large Catholic family from Liverpool).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never thought it was this dangerous, thanks for sharing!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kinda interesting

LikeLiked by 1 person

Every time I find a young person on my family tree who died in 1918, I wonder if they were a victim of this pandemic. I think it’s very possible that something similar can happen today. Interesting post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s entirely possible, particularly with global travel so easy. There has recently been the first 2 cases of Monkey pox in the UK!

The programme on TV tonight hypothesised that an American soldier in Kansas was patient zero and he in turn infected the troops about to sail to war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was horrifying, wasn’t it? Hard to imagine those numbers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awful, and to come on the back of the First World War when people and morale were already depleted, it was such a dreadful event.

LikeLike

Heartbreaking.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So the Spanish flu is not so Spanish, after all. Interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“One quarter of the British population was affected during the epidemic” How does this figure compare with the plague in the 1300s? Was the Spanish Flu more contagious? Obviously increased population and travel helped spread the Spanish Flu, but in villages hit by the plague, were the transmission rates higher than 25% ? I’ve lived in fear of a plague-like epidemic since I was a kid. When the bird flu was the big thing, I bought a mess of surgical masks because I thought everyone was going to be contagious.

LikeLike

Such great info… helped to correct some mis-ideas I had about the Spanish flu. I did not realise it was worse than the plague, nor the reason behind its name. Thanks.

LikeLike