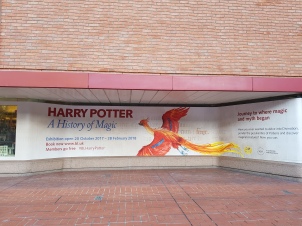

Harry Potter: A History of Magic exhibition at the British Library, for those that don’t know – a stone’s throw from King’s Cross Station, has been open since 20 October 2017 and will close 28 February 2018. It celebrates the twenty years since the release of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Photography is prohibited, as it is at many institutions that house precious artefacts, for the flash can damage fragile documents and mere hours of daylight can constitute a year’s worth of damage.

The exhibition highlights handwritten notes, original drawings and early manuscripts of the phenomenally successful Harry Potter novels and juxtaposes them alongside historic manuscripts and artefacts from British, European, African, Asian and Middle-Eastern cultures. It also displays artwork and portraiture from Jim Kay, whose work adorns the new illustrated versions marking the anniversary. It is where fictional witchcraft and wizardry meet factual notions of witchcraft from more credulous times and cultures.

The exhibition comprises of ten low-lit thematic rooms, chambers if you will, with secrets waiting to be revealed. Great for adding atmosphere for the excited youngsters who visit with their parents, not so much for the myopic forty-something. The visitor traverses the Hogwarts curriculum through each chamber and is taught the rich foundations of subjects that inspired the Potter stories.

You begin in an antechamber entitled The Journey and immediately your eyes are drawn to the flying books suspended from the ceiling. It is situated at the top of a staircase, fortunately, or is it unfortunately?, one that does not reorientate itself mid-flight. The visitor is then treated to a 1991 drawing of Harry and the Dursleys and an annotated sketched map of the grounds of Hogwarts including the school, quidditch pitch, lake and the forbidden forest, J.K. Rowling demonstrating further talents as she plotted out the complex wizarding world and the seven Potter books. The original synopsis of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is there, including the typo ‘astonomy’ instead of astronomy. Present also is the note described below.

‘The excitement in this book made me feel warm inside. I think it is possibly one of the best books an 8/9 year old could read.’

Alice, daughter of a Bloomsbury Chief Executive after reading the early chapters her dad brought home. The next day he agreed to publish Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

You head downstairs to the Potions room where upside-down cauldrons are suspended from above in a bastardised candelabra, of sorts. As a centrepiece it’s striking, as an illuminator, not so much, it’s there for the aesthetic. Displayed here is the Battersea Cauldron. It is questionable whether it was even used for the purpose of witchcraft or potion making, but it is possible that it was a votive offering to the gods 3,000 years ago. It was recovered from the River Thames in 1861, at Battersea. We also see Ulrich Molitor’s On Witches and Female Fortune Tellers, published in 1489, the earliest printed depiction of witches with a cauldron. From the Potter world we can peruse a draft of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince with Rowling’s and her editor’s notes scrawled in the margins.

Heading into the Alchemy room you see a carved head of a unicorn, an eighteenth century apothecary sign, with a narwhal tusk depicting the unicorn’s horn. Narwhals were known as the ‘unicorns of the sea’. Unicorns were believed to hold medicinal qualities and we are reminded that in the Philosopher’s Stone that Voldemort survives on drinking unicorn blood. Then the Potter and ancient worlds meet for displayed is a real bezoar stone – historically kept in elaborate cases. Bezoar stones were mentioned by Professor Snape in Harry’s first potions class and was used to save Ron’s life in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. My joint favourite in this section are the seventeenth or eighteenth century Spanish apothecary jars, one labelled ‘Sang’ Draco V’ to contain dragons blood and Nicolas Flamel’s fifteenth century Parisian gravestone.

The Herbology room is decorated in a similar vein to the previous rooms, terracotta plant pots float above. However, the historical uses of plants has a much more solid footing than some of other lessons in the Hogwarts curriculum. We see J.K. Rowling’s cartoon of Professor Sprout in her greenhouse and Nicholas Culpeper’s English Physician and Complete Herbal, from 1652, which influenced Rowling’s naming of the spells and potions. Culpeper, an unlicensed apothecary, was tried and then acquitted for witchcraft in 1642, demonstrating clearly that playing about with plants and potions was akin to witchcraft in the seventeenth century. This section is resplendent with natural history books, and even a real mandrake root, that does indeed look like an ancient carving of the human form kneeling. In Harry Potter the screaming mandrake is fatal to those who hear it and used correctly it is a powerful restorative; in reality the root and leaves are poisonous.

In Charms we see the visualisation of Diagon Alley, by Jim Kay a stunning panoramic black and white drawing of a quaint hotchpotch of shops, and back to J.K.Rowling’s personal archive of notes for her series – who would have guessed that the Sorting Hat was not the first choice to sort the students into houses? There were several other ideas before settling on the Sorting Hat, including the statues of the four founders of Hogwarts coming alive and selecting students for their houses. Broomsticks are indelibly linked to witchcraft and are integral to the Potter stories, on display is one once owned by an English witch. We also see a thirteenth century manuscript depicting the spell abracadabra, believed to be a cure for malaria.

In Astronomy we enter the world of the stars, where the Hogwarts students take Astronomy classes late at night. Students of astronomy would know that J.K. Rowling was inspired by the heavens when naming some of her characters at Hogwarts, including the astronomy professor Aurora Sinistra and Sirius Black. Displayed is the Dunhuang Star Atlas, circa 700 A.D., a scroll, found in a cave in 1907 that depicts 1,300 stars of the Northern Hemisphere. We also can view the medieval manuscript, An Astronomical Miscellany, and read about the constellation Canis Major – the brightest star from that constellation is Sirius, also known as the Dog Star. Fans of Harry Potter will know that his godfather Sirius Black was an animagi who could turn himself into a black dog.

Pièce de résistance is Leonardo Da Vinci’s Notebook, circa 1506-08, with diagrams of the sun, moon and earth.

In Divination we learn how other cultures attempted to see into the future under hanging tea cups and saucers! Divination has been practised for millennia, however, its efficacy is suspect in these less credulous times. We see examples of palmistry, tarot cards, crystal balls and also an early twentieth century witch’s scrying mirror loaned to the British Library from Boscastle’s Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, who also donated other artefacts on display at the BL. There is also a fourteenth century English manuscript, with exquisite diagrams educating the reader in palmistry and a 1920s Scottish guide to reading tea leaves.

In Defence Against the Dark Arts we see another of J.K. Rowling’s drawings, this one portrays Hagrid, Dumbledore and Professor McGonagall peering at baby Harry cradled in Hagrid’s arms. Encased in protective perspex is a thirteenth century bestiary manuscript that depicts a snake charmer. Snakes, long believed to be magical creatures are also seen decorating a serpent staff made from bog oak that was buried and preserved for centuries and a serpentine wand for spell casting. Werewolves are depicted in Johann Geiler von Kayersberg’s, Die Emies (The Ants) from 1516. Geiler gave seven reasons why werewolves would attack and argued that the likelihood of being bitten by a werewolf was determined by its age and experience of eating human meat. We then encounter Jacobus Salgado’s A Brief Description of the Nature of the Basilisk, who noted that they were ‘yellow, with a crown-like crest and the body of a cockerel attached to a serpents tail’ and warned readers to avoid the glare of the basilisk. From Europe, we then are taken east to see a Japanese water demon, the Kappa, who, according to Newt Scamander, ‘inhabits shallow ponds and rivers’. Scamander, embodying the tradition of the pioneering naturalists exhibited in this exhibition, discusses the Kappa in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

In Care of Magical Creatures we are shown how J.K. Rowling imagined Nearly Headless Nick and Peeves to look back in 1991, and a hand-written draft of Harry, Ron and Hermione escaping from Gringotts on the back of a Dragon in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. In renaissance Italy a ‘monstrous dragon’ was discovered near Bologna in 1572 and naturalist and collector Ulisse Aldrovandi studied the remains, but his discourse remained unpublished until 1640. Toads, among other small animals have long been recognised as witches’ familiars. In Harry Potter: A History of Magic, is an 1824 depiction of a South American ‘toxic toad’, the Bufo auga or giant marine toad.

We are also introduced to the bird-eating spider that Maria Sybilla Merian discovered in Surinam between 1699 and 1701. Reputedly this was the first expedition led by a woman and her Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705) showcased her study of insects in the Dutch Colony. She was derided as a fantasist, even with hearty sales, but the confirmation of bird-eating spiders did not come until 1863.

Displayed also, is a thirteenth century manuscript which depicts a phoenix rising from the flames. Phoenixes have long been associated with mythology and in some cultures they represent Christ’s resurrection. Displayed is a French illustrated manuscript by Guy de la Garde from 1550, L’Histoire et Description du Phoenix, dedicated to Princess Marguerite, the sister of King Henri II of France. We can gawp in horror at the terrifying eighteenth century Japanese mermaid, whose usual home is the British Museum, long now discovered to be a fake; part monkey, part fish. Here it is revealed in a draft, a scene later deleted from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, that Harry and Ron originally crashed Ron’s dad’s car into the Hogwarts lake rather than the Whomping Willow and were rescued by merpeople. The oldest recorded merpeople were known as sirens and a depiction of one is exhibited from a seventeenth century ‘game book’, possibly a love token.

The exhibition concludes with the Past, Present and Future and a display of Harry Potter novels and their derivatives including their many translations resulting from their global success. Extensive plans for Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix are highlighted and a first edition sold at auction in 2013 that has been annotated by J.K. Rowling to further inform the reader. This unique text has also been subject to Rowling’s doodles and here we glimpse a miserable looking profile of Professor Snape. We also see an annotated draft of the screenplay of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and look forward to the future as the franchise continues and refuses to let J.K. Rowling rest.

You can book tickets by clicking this link to the BL here.

Sources

Harry Pottter: A History of Magic, British Library Exhibition, 7 January 2018

Harry Potter: A History of Magic, British Library, Bloomsbury, 2017

Thanks 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds like a fun exhibit – too bad I live so far away! I loved (and have) all the Potter books.

LikeLiked by 2 people

They did a BBC TV programme on it. I’m not sure if that can be picked up on the internet outside the UK.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Omgosh that place sounds amazing! I wish I could see it myself

LikeLiked by 2 people

It was. It’s very popular and all the weekend dates sold out quickly and I had to book time off work to go. I needed to cancel those dates and by the time I could go again they’d introduced Sunday dates which made it so much easier for me. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

This exhibition sounds amazing! I like that they matched Harry Potter with authentic information. It makes it so much more accessible for general public to understand, learn and enjoy.

I’d love to see it!

So what about dragons? Did they really exist? 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

I liked that too. I studied witchcraft and magic as part of my history degree, so as a HP fan I was desperate to see it. I would have like more on witches, but then that would probably have taken away from the HP aspect and the witch crazes could probably have their own exhibition. I’d like to see something on the dragon they found in Italy – I suspect it would be found to be something quite normal, unfortunately. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow!

My theory about dragons is that’s how people preserved the memory of dinosaurs.

I had the same thought about witches – I’d love to learn more. Maybe, you could write a post about them?

I am not really knowledgeable about history but I have respect for it. The older I get, the more interested I become. My major has been literature with the focus on the contemporary.

I also love HP series! I can’t believe it’s 20 years since they were published.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I do have a little witchcraft post. I’d love to write more. I like to use primary sources and although I’ve lots of books I’d prefer using original documents so I’d have to find where they are archived.

https://historianruby.wordpress.com/2017/10/18/witchcraft-petty-treason-and-poisoner-women-on-trial-at-the-old-bailey-london/

LikeLike

This sounds amazing. Combining HP and history. And it sounds like it was visually all stunning, too. Artsy. Thanks for sharing. I can’t go, so your post transported me there quite well.

LikeLike

This is AWESOME 🙂 Wish I could have been there. Does this happen often?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think this was a one-off. They had announced it about a year before. The planning involved in researching these exhibitions is immense.

LikeLike

sounds amazing! lucky you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLike

This is a fantastic review of an equally amazing exhibition! I’m so glad you had a good time at it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just found your blog. I absolutely love your posts. So much to see and read over here! Will definitely be visiting you more often 🙂

All the best in 2018.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much! 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw the television programme and really wanted to get the exhibition. I don’t think that’s going to happen now, but your wonderfully evocative writing makes me feel like I’ve just been round it. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It really does highlight the depth of the research that J K Rowling did to write the series.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much 🙂

LikeLike

Oh, my god, this is the best exhibition ever!!!

I wish I was in London at that time… 😦 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I wish I could go back to see it!!! Nice to see it on your post though : )

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was special. I wasn’t very well when I went to it but I was determined to see it 🙂

LikeLike

Sounds good! I didn’t hear about it until too late and it had sold out 😦 Thanks for the insight though, makes me feel more like I’d got to go!

LikeLiked by 1 person