This article was first published on history@kingston, February 2015

So much of London’s fascinating black history is hidden from the historical record, so when I noticed the phrase ‘Black Boy’ written in the minutes of the Philanthropic Society during research for my recent MA dissertation on juvenile delinquency and philanthropy in the late eighteenth century, I was intrigued. It was the first time that I had encountered the mention of a black person in my archival research, and thus thirteen-year-old Thomas West’s admission into the Philanthropic Society caught my attention.

Aiming to deter criminality in the hordes of children who lived in London’s slums, the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1788, housed destitute or vagrant children, the children of criminal parents and child criminals. The ‘objects’ of the Society were apprenticed to tradesmen, such as a shoemaker, carpenter and printer, who were employed to school the children in trades that promised self-sufficiency in adulthood. Many of the Society’s benefactors would recommend children that they thought worthy of receiving succour from the Society, which included regimented labour in its workshops and moral religious instruction.

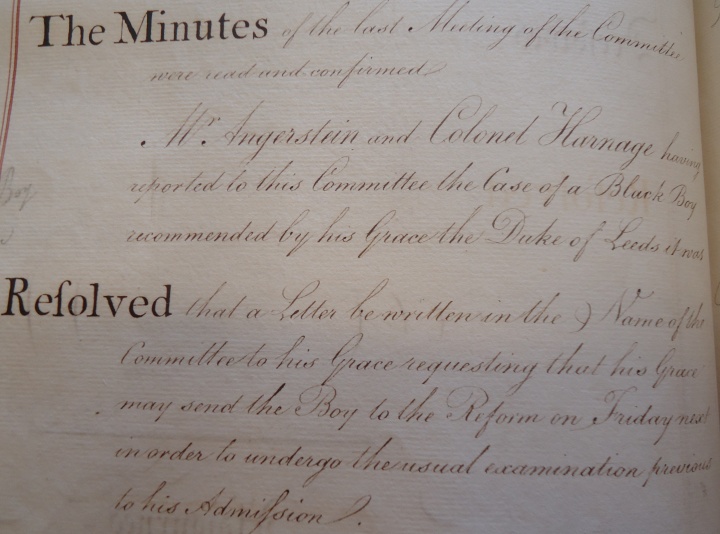

Little is known of Thomas’ background. Evidence suggests that he was a servant in the household of Lord Sydney until he was accused of the thefts which terminated his employment. Initially, his case was brought before the general committee meeting of 17 May 1793, reporting that an unnamed ‘Black Boy’ was recommended for the Society’s guardianship by its President, the Duke of Leeds. Subsequently, a letter requested the attendance of ‘the boy to the Reform on Friday next’ to undergo an entrance examination. (‘Reform’ was the term used by the society to describe the reformatory houses).

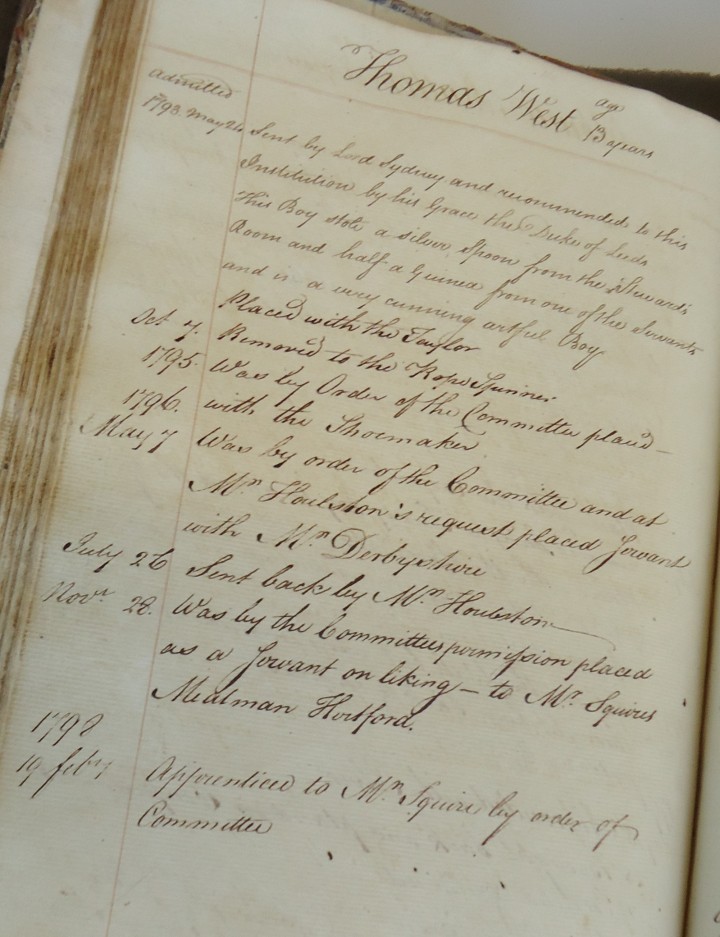

After a successful examination, Thomas was immediately admitted into the Society’s care on 24 May 1793 and was placed with the tailor. His admittance was recorded in the Characters of the Boys Admitted into the Reform register, in which he was described as a ‘very cunning, artful boy’, having stolen a silver spoon from the Steward’s Room and half a guinea from one of the servants of Lord Sydney. Unlike others admitted into the Society, there is no mention of Thomas’ family in the register illuminating his origin, so we are left to speculate on an English birth, colonial ties or links to the African continent.

Thomas stayed with the tailor for over two years before moving to the rope-spinner in October 1795, but for reasons not noted, he then moved to the shoemaker. In May 1796 by order of the committee, he was placed as a servant with a Mr Derbyshire. However, he returned to the Philanthropic Society two months later.

In November 1796, the Society’s meal-man, applied to the Superintendent for Thomas to be placed as a servant with him for an annual wage. Permission granted, Thomas was placed on approval with Hertford based Mr Squires, suggesting that he had formed a rapport with Thomas during his visits to the Reform, resulting in his request for Thomas to join his service.

Thomas’ record in the Characters register, which shows him being placed in domestic service, is unusual for the boys of the Philanthropic Society. Research into the Society’s early years demonstrates that boys generally were apprenticed within the first two years of admission, although variables included the age of the child on admission, how disruptive they were and an aptitude or desire for a particular role. The female Reform, by comparison, demonstrates that domestic servitude was the limit of their ambition for girls.

Was this the same for the ‘Black Boy’? Was it unusual that a well-behaved boy, with no infractions noted against him, was not apprenticed to a trade? Was this disparity a recording omission or a racially motivated tactic? Speculating further, this may not have been a prejudice born of skin colour, but of language, for if he was African born, a poor command of English may have been an obstacle to learning a trade. However, Thomas lived at the Society for several years, and had earlier lived in a gentleman’s household; suggesting that language was not a barrier and therefore another undetermined reason prevented Thomas practising a trade within the Society. It is impossible to definitively state that Thomas’ treatment was shaped by racial prejudice, for while Thomas was called the ‘Black Boy’ in the committee meetings, nowhere is Thomas’ heritage noted in the Characters book, suggesting that for those living in the City of London, who would encounter people of different nationalities with some frequency, darker-skinned people were not unusual enough to be documented in a ledger.

Thomas’ story within the history of the Philanthropic Society ends in February 1798 when he was apprenticed to Mr Squires. Whilst it is only possible to trace Thomas West through his five years in the care of the Philanthropic Society, for his records cease on his apprenticeship, his evolution from the unnamed ‘Black Boy’ sliding into delinquency, into Thomas West apprentice meal-man, offers an otherwise hidden tale of triumph that enriches the narrative of Black Britain.

Suggested Reading

Kathleen Chater, Untold Histories (2009)

Muriel Whitten, Nipping Crime in the Bud (2011)

https://historyatkingston.wordpress.com/

Primary Documents

Surrey History Centre, Philanthropic Society, 1788 Characters of the Boys Admitted into the Reform, 2271/10/1

Surrey History Centre, Philanthropic Society, Trade and Finance Committee Minutes, 2271/7/1

What an interesting dissertation! Don’t know if I overlooked it, but what is your MA in?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi thanks! My Master’s was in History. My dissertation was a study of the Philanthropic Society – Disorderly Children and the Philanthropic Society’s Attempts to Reform them, 1788 – 1820. Thomas West was one of their ‘subjects’.

LikeLike

I like this article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I’m glad you do.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on HistorianRuby and commented:

Reblogging this in honour of black history month.

LikeLike

Are there no records of Thomas in the census?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s difficult to find. The earliest modern census is the 1841 census and his age and common name probably hinder his being found. The early censuses are nowhere near as detailed as later ones and if I’m not mistaken, other historians have tried to find him and drawn a blank.

LikeLiked by 1 person